Chukchi Plateau

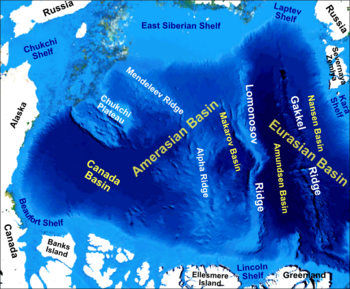

The Chukchi Plateau or Chukchi Cap is a large subsea formation extending north from the Alaskan margin into the Arctic Ocean. The ridge is normally covered by ice year-round, and reaches an approximate bathymetric prominence of 3,400 m with its highest point at 246 m below sea level.[1] As a subsea ridge extending from the continental shelf of the United States north of Alaska, the Chukchi Plateau is an important feature in maritime law of the Arctic Ocean and has been the subject of significant geographic research. The ridge has been extensively mapped by the USCGC Healy, and by the Canadian icebreaker CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent (with the Healy) in 2011 and RV Marcus Langseth, a National Science Foundation vessel operated by the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University.

Geology

[edit]The cap is normally ice-covered, year-round.[2] The cap lies roughly about 800 kilometres north of the Point Barrow, Alaska.[3] The area is notable because it is believed to be rich in natural resources (especially oil, natural gas and manganese).

The geologic history of Arctic Ocean basins is a major source of debate among marine geophysicists. The difficulties associated with collecting marine geologic and geophysical data in this remote region has added to the debate on the tectonic history of the Arctic Ocean and the formation of its bathymetric features.

The Chukchi Borderland, which comprises the subsea region north of the Alaskan coast as well as the bathymetric highs of the Chukchi Plateau and the adjacent Northwind Ridge, is a continental fragment that is thought to have drifted from the Canadian continental margin.[4] The geomorphology of the region is defined by north–south trending normal faulting[5] –tectonic activity typical of continental rifting.

Although there is no consensus as to the pre-rift location of the Chukchi Borderland, its tectonic migration could be attributed to an inferred spreading center indicated by a linear gravity low in the Canada Basin [citation needed]. Sediments transported from the Mackenzie River Delta would have buried the spreading center. The Chukchi Plateau, which could have been connected to Canada in the vicinity of Ellesmere Island, would have rifted along the spreading center to its current location.[6] A competing hypothesis suggests that the Chukchi Plateau may have once been attached to the Siberian shelf.[7]

The Chukchi Plateau also shows substantial evidence of pockmarks, which indicates subsurface hydrocarbon activity.[8]

Law of the sea implications

[edit]

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, party states may submit claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend its continental shelf beyond the 200-mile buffer that comprises a state's exclusive economic zone.[9] This requires that the proposed extension be a natural prolongation of the state's continental shelf, which can be concluded through bathymetric mapping and analysis. If a state can prove that a subsea formation is a natural prolongation of its continental shelf, it must consequently locate the foot of the slope, the physical boundary between the natural prolongation and the abyssal plain of the ocean basin. The foot of the slope is then applied to two equations that inform the claim made by a state for the legal extension of its continental shelf.[9]

The first equation calculates the Hedberg Line, which is derived by adding 60 nautical miles to the foot of the slope of the natural prolongation. The second yields the Gardiner Line, which refers to the point at which the measurement of subsea sediment thickness is 1% of the distance back to the foot of the slope. The two formulae for deriving these values can be substituted in order to form a composite continental shelf for a coastal state that yields the most advantageous possible maritime territory extension.[9]

The United States has not ratified UNCLOS, although there is a concerted, bipartisan effort in Congress and among the various branches of the United States Military to do so.[10] On May 10, 2013, the Obama White House released the National Strategy for the Arctic Region, which supported ratification of the treaty.[11] If the United States were to accede to UNCLOS, they would accrue the exclusive rights to exploit the natural resources on and under the continental shelf.[8] Some potentially extractable resources include manganese and metallic sulfides, oil, gas and gas hydrates, and sedentary species such as mollusks and clams.[8]

USCGC Healy expeditions

[edit]

Since 2003, USCGC Healy has undertaken eight expeditions to the Chukchi Sea with researchers from the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center at the University of New Hampshire and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[12] The cruises investigated the bathymetry of the Chukchi Borderlands in order to inform discourse involving the potential ratification of UNCLOS by the U.S.

The latest cruise (HEALY-1202), lasting from 25 August to 27 September 2012, traversed 11,965 km of the Arctic Ocean and mapped about 68,600 km2 of the seafloor. The Healy was equipped with multi-beam sonar devices and seismic measurement devices, and was crewed by a 34-person scientific party and around 100 US Coast Guardsmen. The expedition collected 10,030 km (5,416 nm) of multi-beam sonar data.[13] HEALY-1202 began in Barrow, Alaska, reached a northernmost point of 83° 32’ N, 162° 36’ W, and culminated in Dutch Harbor, Alaska.[14]

Prior to the Healy cruises, the foot of the slope of the US continental shelf was believed to lie at the margin of the Chukchi Plateau. The cruises revealed that the foot of the slope was significantly further north at 81° 15’ N and a depth of approximately 3,800 m[15]–the boundary of the Northern Chukchi Borderland with the Nautilus Basin.[8]

In 2011 scientists aboard sea vessel, Marcus G. Langseth, ran tests to increase understanding of the geology, structure and history of the continental shelves running underwater off Asia and North America, and the Chukchi Borderland, an adjoining region of dramatic deep-sea plateaus and ridges some 800 miles from the North Pole. One test includes sending sound pulses to the seabed and reading the echoes.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Mayer, Larry; Andrew Armstrong (September 28, 2012). "U.S. Law of the Sea cruise to map and sample the US Arctic Ocean margin" (PDF). Center For Ocean and Coastal Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center, University of New Hampshire. p. 4. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Marie Darling, Donald Perovich. "CRREL scientists complete Arctic voyage of discovery". United States Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. "United States Explores the Seabed of the Arctic Ocean: to bolster its Claims to the North's Strategic Resources". Canadian American Strategic Review. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hall, John K. (1990). "Chapter 19: The Chukchi Borderland". In Grantz; Johnson; Sweeney (eds.). The Arctic Ocean Region. The Geology of North America. pp. 337–50.

- ^ Grantz, A.; et al. (1998). "Phanerozoic stratigraphy of Northwind Ridge, magnetic anomalies in the Canada basin, and the geometry and timing of rifting in the Amerasia Basin, Arctic Ocean". GSA Bulletin. 110 (6): 801–20. Bibcode:1998GSAB..110..801G. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1998)110<0801:PSONRM>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Lawver, L.A. (2011). "Chapter 5 Palaeogeographic and tectonic evolution of the Arctic region during the Palaeozoic". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 35: 61–77. doi:10.1144/M35.5. S2CID 129968291.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Betsy (14 November 2013). "The Arctic Continental Shelf: Science & Law in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea". Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska–Anchorage. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c "United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea" (PDF). p. 53. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Patrick, Stewart (June 10, 2012). "(Almost) Everyone Agrees: The U.S. Should Ratify the Law of the Sea Treaty". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "National Strategy for the Arctic Region" (PDF). whitehouse.gov. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2017 – via National Archives.

Strengthen International Cooperation – Working through bilateral relationships and multilateral bodies, including the Arctic Council, we will pursue arrangements that advance collective interests, promote shared Arctic state prosperity, protect the Arctic environment, and enhance regional security, and we will work toward U.S. accession to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Law of the Sea Convention).

Alt URL - ^ "Law of the Sea". Center for Ocean and Coastal Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center, University of New Hampshire. 18 July 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Mayer, Larry; Andrew Armstrong (September 28, 2012). "U.S. Law of the Sea Cruise to map and sample the US Arctic Ocean margin" (PDF). Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center, University of New Hampshire. p. 24. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Mayer, Larry; Andrew Armstrong. "U.S. Law of the Sea cruise to map and sample the US Arctic Ocean margin" (PDF). Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center, University of New Hampshire. p. 1. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Mayer, Larry; Andrew Armstrong (September 28, 2012). "U.S. Law of the Sea Cruise to map and sample the US Arctic Ocean margin" (PDF). Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center, University of New Hampshire. p. 8. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ blogs.ei.columbia.edu